Inflation & Targeting ‘Food Security for all’ through Public Distribution System of India

“We know that a peaceful world cannot long exist, one-third rich and two-thirds hungry.”

— Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States of America.

Creating the harmonious, peaceful and developed world economy is challenged by the widespread inequalities of different sorts, absolute as well relative. Food which is a basic necessity of human beings is found unequally distributed and millions of people are deprived from it. This phenomenon worsens with increase in the cost of living, that is, inflation, and makes basic items such as food costlier to consume.

Hence to target reducing inequalities in a nation, the Government, benevolent actor of Modern Welfare State has taken multiple responsibilities and food security for all is one among them.

This article aims to provide insights on how the Public Distribution System (PDS) in India acts as a direct point of contact between the government and the people, acting as a navigator amid high volatility in food inflation.

The vagaries of food inflation and its high weightage of 47.25% in the CPI basket have made the role of public distribution system even more significant for the Indian economy.

Notwithstanding the fact that food inflation has eased from 11.51% in July to 9.94% in August, the uncertainties in the outlook of cereals and pulses supplies due to El Nino situation over the upcoming quarter has added pressures on the government to zero in on the PDS network.

What is PDS?

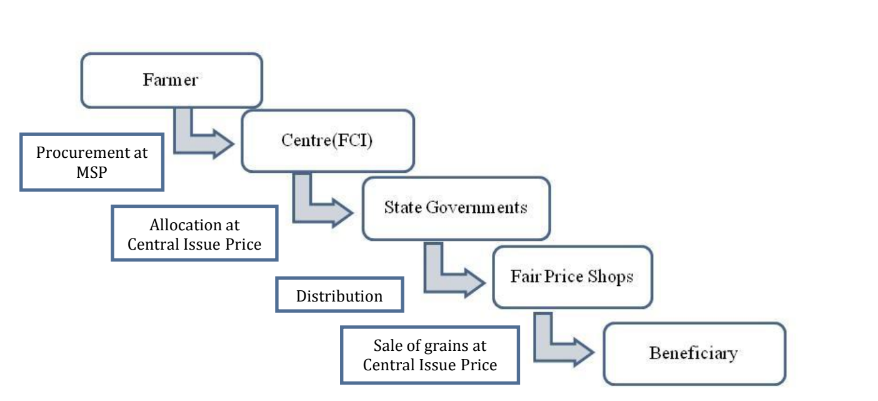

Public Distribution System is a system for managing food scarcity through distribution of food grains at reasonable rates working as the strategy to achieve food security for all in India. It is operated by two-levels of governments, the Central and State Governments jointly.

The responsibility of procurement, storage, warehousing, transportation and bulk allocation of food grains to state governments rests with the Food Corporation of India (FCI). Operational responsibility of allocating food grains within the State, identification of eligible families, issue of Ration Cards and supervision of the functioning of Fair Price Shops (FPSs) etc., rests with the State Governments.

With the launch of Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) in June 1997, the government aimed to channelize the food subsidies towards the poorer sections of the population, i.e., the Below Poverty Line families. This was further augmented through the enactment of National Food Security Act, 2013, which relied largely on the existing TPDS network to deliver food grains as legal entitlements to poor households.

In order to make TPDS more focused towards the poorest segment of BPL population, the “Antyodaya Anna Yojana” (AAY) was launched in December, 2000 for one crore poorest of the poor families.

According to the Department of Food and Public Distribution, the total number of beneficiaries stand at 80.18 crore out of which 8.54 crore beneficiaries are covered under AAY.

Procurement Dynamics

Before the harvest, during each Rabi / Kharif Crop season, the Government of India declares the minimum support prices (MSP) for procurement on the basis of the recommendation of the Commission of Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) which along with other factors, takes into consideration the cost of various agricultural inputs and the reasonable margin for the farmers for their produce.

According to Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution, the following mechanism for procurement is prescribed:

- Centralised (Non-DCP) procurement system: Under the centralised procurement system, the procurement of food grains in Central Pool is undertaken either by FCI directly or by State Govt. Agencies (SGA). Quantity procured by SGAs is handed over to FCI for storage and subsequent issue against GOI allocations in the same State or movement of surplus stocks to other States. The cost of the food grains procured by State agencies is reimbursed by FCI as per Provisional per cost-sheet issued by GOI as soon as the stocks are delivered to FCI.

- Decentralised (DCP) Procurement: The scheme of Decentralised Procurement of food grains was introduced by the Government in 1997-98 with a view to enhancing the efficiency of procurement and PDS and encouraging local procurement to the maximum extent thereby extending the benefits of MSP to local farmers as well as to save on transit costs. This also enables procurement of food grains more suited to the local taste. Under this scheme, the State Government itself undertakes direct purchase of paddy/rice and wheat and also stores and distributes these food grains under NFSA and other welfare schemes. The Central Government undertakes to meet the entire expenditure incurred by the State Governments on the procurement operations as per the approved costing.

The Government has fixed relatively higher MSP for pulses and oilseeds to meet the nutritional requirements and changing dietary patterns and to achieve self-sufficiency.

Rising Food Subsidies and Tightening Government Budget

To cover the costs incurred by FCI on procurement, storage and distribution, the centre provides subsidies as remuneration.

According to a report by PRS:

“In 2021-22, FCI has claimed Rs 2,17,460 crore as food subsidy which is 95% of the food subsidy bill for the entire year. Against this, in the revised estimate of 2021-22, the central government has provided Rs 2,10,929 crore which is lesser than the subsidy claimed by FCI. In 2022-23, the central government has allocated Rs 2,06,831 crore for food subsidy out of which Rs 1,45,920 (71%) crore is for providing food subsidy to FCI”.

Since April 2020, the government has been implementing the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) in phases. Under the programme, which was announced in March 2020, the government has allocated an additional 5 kg of wheat or rice to 80 crore people free of cost under the National Food Security Act, 2013. This is over and above the monthly entitlements under the National Food Security Act, adding further pressures to the food subsidy bill by an estimated Rs 53,345 crore.

Food subsidy is the largest expenditure by the Department of Food and Public Distribution.

According to FCI, it has three major elements:

- Consumer Subsidy = (Economic Cost – Central Issue Price)* Quantity of food grains issued under different schemes

- Buffer Carrying Cost i.e. a part of the operation cost apportioned to buffer stock based on excess stock held over and above operation stock (four months sale).

- Subsidy on coarse grains, regularisation of operation losses of Food Corporation of India and other non-plan allocation to State Governments.

State Wise Procurement of Rice and Wheat for Current Market Season

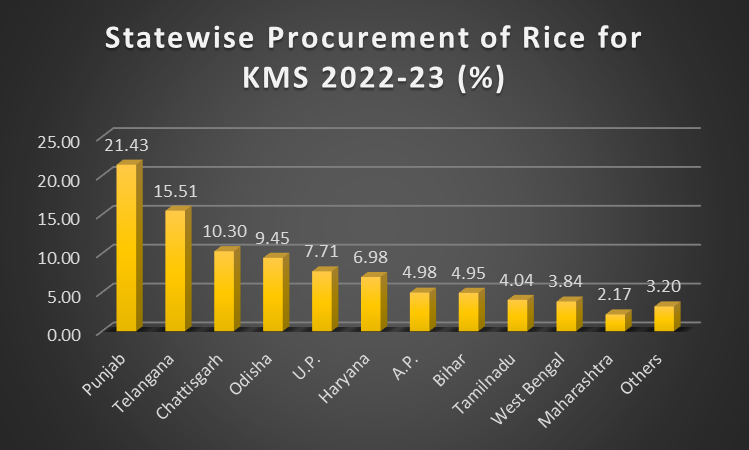

Rice

The bulk of rice procurement is concentrated on 6 major states- Punjab, Telangana, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana, accounting for 71.38% of FCI’s total procurement. However, the contribution of these states in the total production of rice is less than 45%.

The Centre has set a target to buy 62.60 million tonnes of rice in the 2022-23 marketing season. The FCI had procured 57.58 million tonnes of rice during the 2021-22 marketing season.

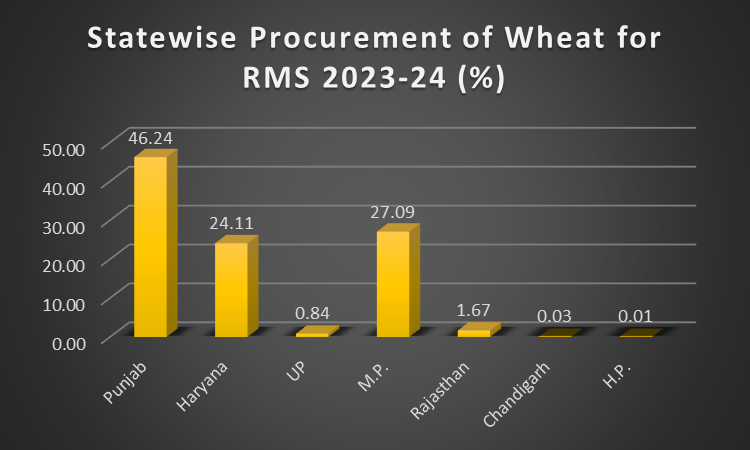

Wheat

About 97.44% of total wheat procurement is concentrated in only three major states- Punjab, Haryana and Madhya Pradesh. However, they contribute less than 40.46% to the total production pool.

According to the Department of Food and Public Distribution, the estimate for procurement of wheat for Central Pool during RMS 2023-24 is 341.50 LMT.

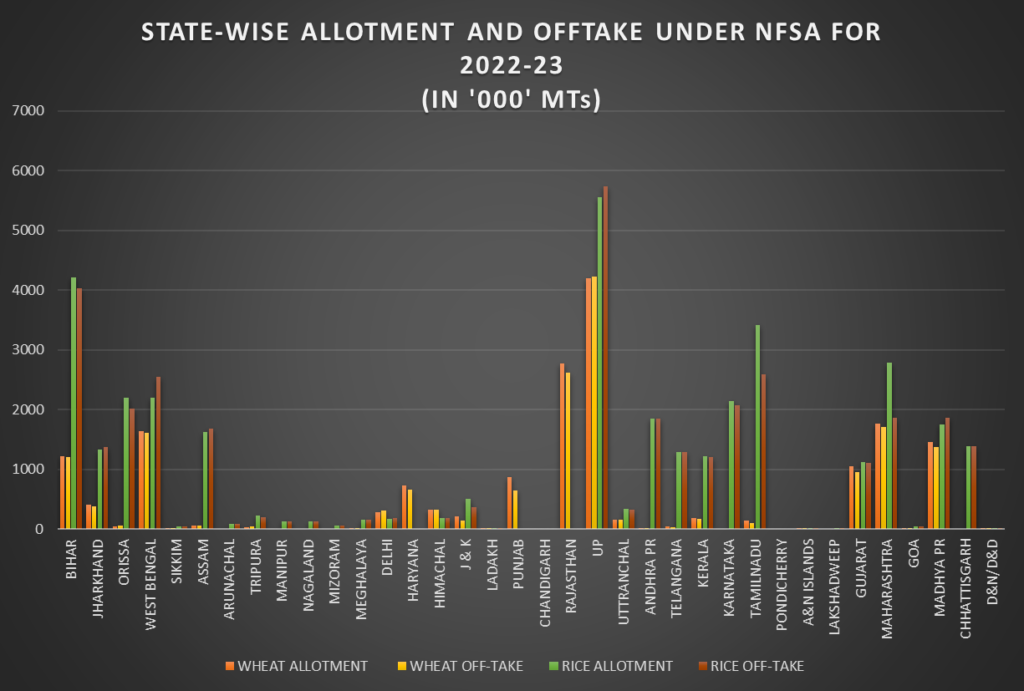

State Wise Allocation v/s Offtake

It can be observed that the allocation of rice is comparatively higher than wheat across different states.

Secondly, the off takes exceeded the allocated quantities in six states for wheat and a staggering high of thirteen states for rice, indicating imbalances in demand-supply situations, especially for water-intensive crops like rice.

It also shows the Centre’s dilemma on managing demands of States under a restricted budget and increasing inflationary pressures.

States like Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar received the highest allocation of wheat while maximum allocation of rice was made for Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, West Bengal and Odisha.

Inflationary Pressures challenging PDS

Recently, the Government of India decided to discontinue OMSS of food grains to States creating panic situation within some State Governments.

- So what is OMSS?

The Open Market Sale Scheme (OMSS) is a program implemented by the FCI to facilitate the Sale of surplus food grains, primarily wheat and rice from the central pool in the open market. State governments/ UTs can participate in e-auctions if their requirement for wheat or rice exceeds the allocation amount. It serves various purposes such as enhancing food grain supply during lean seasons, ensuring food security and availability of grains in deficit regions, controlling open market prices and inflation, facilitating the sale of surplus food grains from the central pool etc.

- Why the Central Government took this decision?

Owing to sharp upswing in mandi prices of rice and wheat in the preceding months, the government decided to discontinue sale of OMSS grains to states, citing price control measures for essential commodities, namely wheat and rice, for curbing inflation and maintaining sufficient stock levels in the central pool.

The OMSS underwent a recent revision with a focus on limiting the quantity that a single bidder can purchase in a single bid. Previously, the maximum allowed quantity per bid was 3,000 metric tonnes. However, it has now been reduced to a range of 10-100 metric tonnes. The aim of this change is to promote wider participation by accommodating small and marginal buyers.

The OMSS operation was started early this year on June 28, in view of the increasing trend of wheat and rice prices. The government announced 15 lakh tonnes of wheat and 5 lakh tonnes of rice sales announced under the OMSS on 2023, June 28. Additionally, the government has decided to offload 50 lakh tonnes of wheat and 25 lakh tonnes of rice in the open market through the OMSS in 2023, August.

Initially, wheat offered for sale used to be 4 lakh tonnes and now, it has been reduced to 1 lakh tonne in e-auction on 2023, August 9. About 8 lakh tonnes of wheat has been sold till date.

The FCI CMD also said that initially, the weighted average selling price of wheat on June 28 was Rs 2,136.36 per quintal, which has now gone up to Rs 2,254.71 per quintal in August’s e-auction. This shows there is an increase in the market demand for wheat.

Rice sale under OMSS was negligible. About six e-auctions for rice have been conducted since July 5 but the offtake has not been up to the mark most likely because of the high reserve price, which is at Rs 31.73 per kg. Therefore, the government has reduced the reserve price of rice from Rs 31 per kg to Rs 29 per kg. In e-auction on 2023, August 9, about 1,500 tonnes of rice has been sold under the OMSS.

- What is the impact of this step on State Governments?

“State governments of Karnataka, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu have requested for wheat and rice under OMSS (D) Policy, which was not acceded to due to the discontinuation of the sale of wheat and rice to states under OMSS(D) 2023”, said, the Minister of State for Food and Consumer Affairs Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti said in a written reply to the Lok Sabha.

- Karnataka’s response– The Centre’s move on revising OMSS restrictions took a massive toll on Karnataka’s Anna Bhagya Scheme which promised 10 kgs of free rice every month to 12.8 million low-income families. It was planning to procure the additional requirement of 228,000 tonnes through OMSS at FCI’s standard rate of Rs 34/Kg. The lapse in procurement forced the state to replace free rice distribution with direct cash transfers.

- Tamil Nadu’s Response– As a result of the aforementioned changes, Tamil Nadu Civil Supplies Corporation (TNCSC) is negotiating with the National Cooperative Consumers’ Federation of India (NCCF) and other States to procure the additional quantity of 50,000 tonnes to 60,000 tonnes a month of rice which was initially planned to be purchased via the regular OMSS route.

While the discontinuation of sale of OMSS grains to states has disrupted the supply chains of various states, it has also encouraged them to find alternate and decentralised sources for procurement of essential commodities, which are more sustainable in the long run. Given the inflationary pressures and climate uncertainties, procurement of grains over and above the FCI allocation remains to be a cause of concern for several states.

Remarks

India’s growth trajectory has been marked by several lessons and accomplishments. India has the largest public distribution network in the world which has ensured the food security of a population of more than 80 crore.

With recent developments pertaining to ‘One Nation One Ration Card’, creation of National Food Security Portal– a centralised database on PDS functioning, Aadhar seeding of ration cards, e-PoS enabled distribution, etc., India is strengthening its PDS network backed by technology. Yet, a lot remains to be done to ensure that the allocated resources reach the target beneficiaries without any leakages and exclusion errors are minimised.

Amid high inflationary situation, India’s PDS network has proven to safeguard national food security to a considerable extent, especially for the vulnerable sections of the population.